Understanding early human development helps scientists study causes of miscarriage and search for therapies and preventions for developmental disorders. As I’ve explained before on this blog, NIH is prohibited from funding research that creates or destroys human embryos. However, models of various aspects of human embryo development represent promising alternatives.

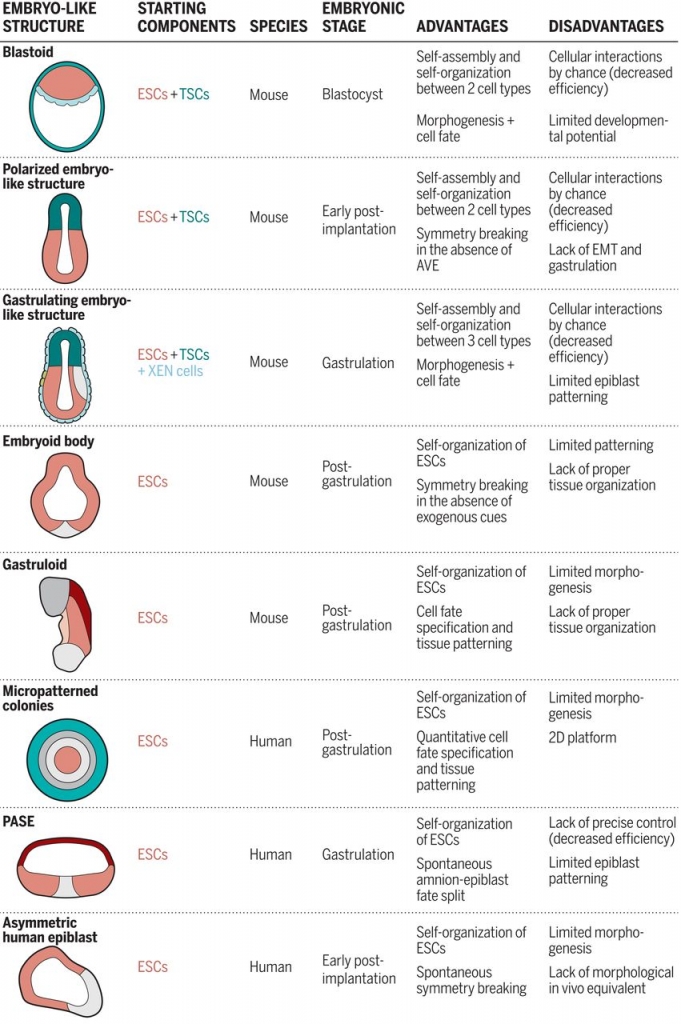

Readers of this blog may recall that in 2019, I wrote about how NIH, as a steward of public funds, carefully considers whether the agency can support proposed research using these models on a case-by-case basis. We at NIH have been following the progress of these various research approaches, and last year my office sponsored a state of the science workshop on these model systems at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. At the workshop, leaders of the field presented their findings and future research plans with models that vary in shape and composition and mimic different aspects of actual embryos and time points in development. The researchers explained how they use these models to investigate how cells differentiate into specific cell types and organize themselves and what signals coordinate key changes during embryonic development. Models range from rings of different cell types in a single-cell monolayer to more spherical models of particular features of the human embryo. (See diagrams of several models below.)

With these new tools developed and further refinements on the horizon, I thought it would be a good time to share our latest thoughts on how we decide what research we can legally support. When NIH considers whether the agency can support a specific research proposal, we ask ourselves (and sometimes the applicants!) a number of questions. These may include:

- What stage, or aspect, of embryonic development is being modeled?

- What cell types, structures, and functions are present in the model? For example,

- Does the model contain all components of the epiblast lineage (i.e. the three “germ layers” that collectively form the embryo)?

- Does the model contain any extraembryonic lineage cell types (i.e. cells that contribute to the yolk sac, placenta, or other tissues that support development of the embryo)?

- Are there other materials or growth factors present that might substitute for the functions of the extraembryonic lineages?

- Is the spatial orientation of the components similar to, or different from, an actual embryo?

- Are the cells in a single monolayer or in a more complex structure?

- How is the shape similar to or different from that of the embryo?

- Can the model maintain its organizational structure? Does it change to look like the next stage in normal development?

- Would the researcher watch for any unanticipated events, such as the unexpected appearance of other cell types or structures?

Ultimately, NIH considers what is the likely developmental potential of the model. This is of course a tricky question, since the ultimate test of the potential of a model would be to study its growth in a uterine environment–an experiment that NIH would never support. Yet we know what structures and functions of an embryo and extraembryonic tissue are critical for development, so we have a framework to address this question.

Personally, it has been fascinating to witness the advancements in this field. As an agency, NIH will continue to consider applications on a case-by-case basis, and do our best to be a responsible steward of public funds.

Summary of Stem Cell Models of the Mouse and Human Embryo

From Shahbazi et al., Science 364, 948–951 (2019). Reprinted with permission from AAAS.